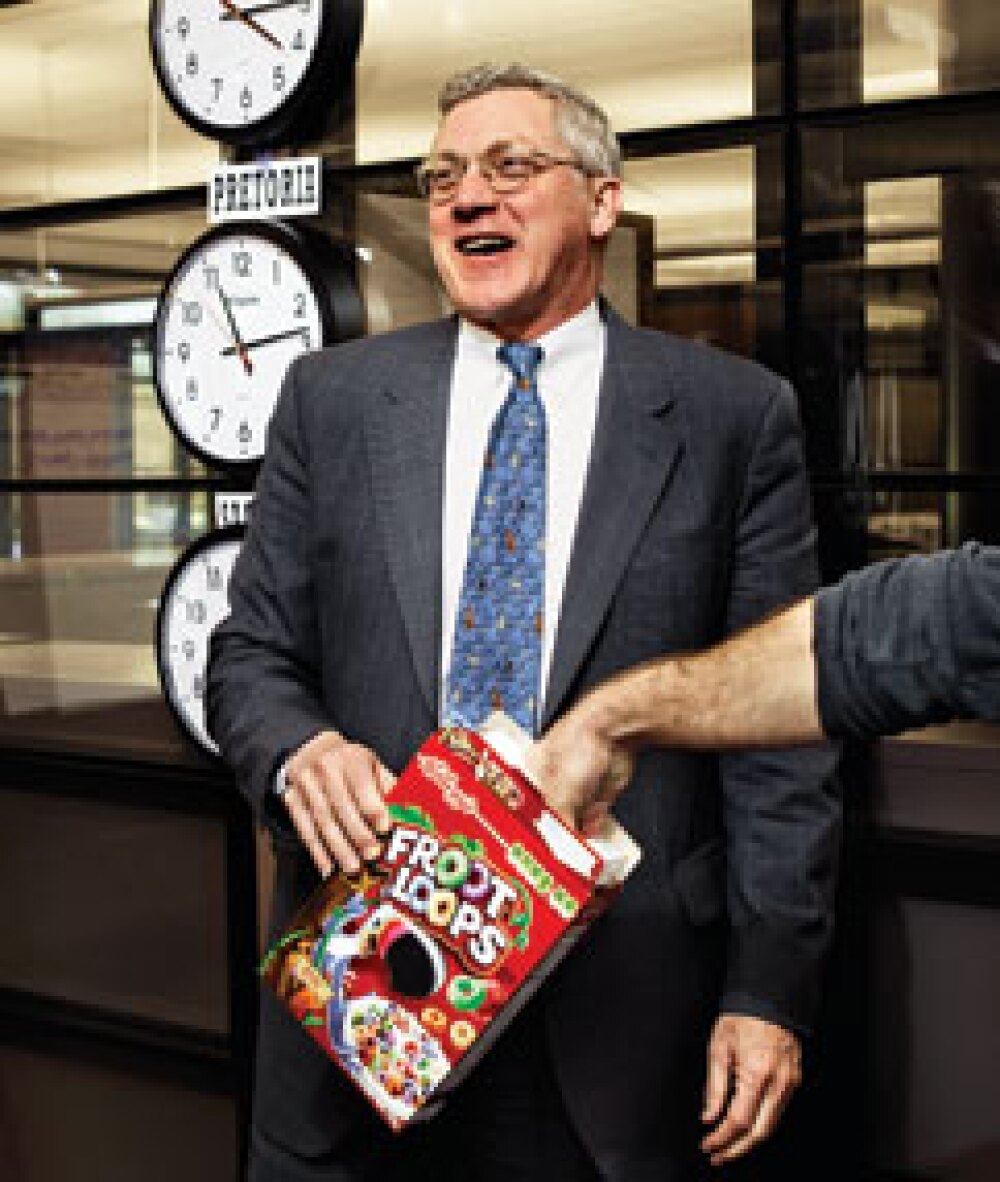

It’s a bitter-cold January afternoon in Battle Creek, Michigan, and Paul Lawler is glued to his computer monitor, grimly reviewing another day of losses in the U.S. stock market. As vice president and chief investment officer of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, Lawler, 60, has a lot to worry about.

“We’re an institution in the middle of the Midwest, facing a severe economic downturn,” he notes. “Yet companies like Kellogg and institutions like the foundation must continue to do a good job providing the necessities of life to the global community.”

Like his counterparts at other foundations, endowments and pension funds, Lawler has seen the value of the assets under his care decline, slowly through the first half of 2008, then straight off a cliff last fall.

That’s a sharp contrast to what was happening in August 2007, when the Kellogg portfolio had a record $8.4 billion in assets. The foundation was able to dispense $335 million that year, the largest distribution in its 75-year history. Unfortunately for the needy children and communities who benefit from Kellogg largesse, however, the credit crisis had just begun, and the foundation — which allocates 5 percent of its assets to payouts — began to shrink. At the end of January, it had $6.4 billion, almost 24 percent below its high-water mark. Lawler had long since gone into crisis mode. He was facing an even bigger hurdle than most of his peers, because much of the portfolio he oversees is beyond his control.

Lawler must grapple with constraints practically unheard of in modern portfolio theory: About 65 percent of Kellogg Foundation assets are completely undiversified, invested in Kellogg Co. common stock (the foundation owns about 25 percent of the cereal and snack food company). That’s not as bad as the 85 percent figure Lawler faced when he came onboard in 1997, but every investment decision he makes is informed by the fact that cornflakes dominate the portfolio. Perhaps more than most investors, Lawler understands the danger of having all his Eggos in one basket and has taken the 35 percent of assets that aren’t in Kellogg shares and put them in a portfolio filled with hedge funds and other alternatives.

At the end of 2007, Lawler could point to a 15.5 percent annualized five-year return on the diversified portion of the portfolio, beating the 12.6 percent performance for endowments and foundations tracked by the Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service. Kellogg stock, by comparison, returned 11.6 percent, and the overall portfolio, 13 percent.

“He has done a very good job figuring out at the macro level what they want to be invested in,” says Marc Lasry, head of Avenue Capital, a New York–based, distressed-asset hedge fund hired by Kellogg in 2006. Lasry says Lawler foresaw the current economic turmoil: “In 2006 and 2007, Lawler’s point of view was that things were going to get worse.”

Foundations that fail to diversify often come to regret it (see related article, “Stuck on Chocolate And Addicted to Coke”). An example that illustrates the point is a classic. In July 2000, Hewlett-Packard Co., a computer hardware manufacturer, was on a roll, caught up in the high-technology euphoria of the time. H-P shares hit their historical high of $67 that month before beginning a long, painful descent to $11 in October 2002 as the tech sector collapsed. Shareholders and employees were the most obvious victims of the evaporating equity, but there was also huge collateral damage to children, scholarship programs, conservation initiatives and the Monterey Bay Aquarium. That was because the David and Lucile Packard Foundation’s once–$18 billion portfolio was invested solely in H-P stock. The foundation’s endowment lost more than 80 percent of its value, programs were slashed, and more than half of the 185 employees were let go (the foundation has since diversified).

The Kellogg Foundation isn’t as shackled as was the Packard Foundation, whose benefactors insisted the charity hang on to all those H-P shares. Will Kellogg, who created the foundation 28 years after starting his namesake company, gave trustees carte blanche to run things however they saw fit. Nonetheless, trustees kept 100 percent of foundation assets in Kellogg stock until an act of Congress forced them to begin diversifying in 1985.

The arrangement between foundation and company, however, is seen as mutually beneficial: Kellogg is supposed to be a safe consumer stock, and it often performs better than the overall U.S. stock market during economic declines. In turn, the foundation’s control of such a big chunk of the company means that Kellogg has a friendly owner insulating it from hostile takeover. “Kellogg wanted to be sure that it would be tough for an outside investor to acquire the company,” explains William Richardson, president and CEO of the foundation from 1995 to 2005.

The perception of safety can be illusory, as the foundation discovered in the late 1990s, when increased competition and ineffective management sent Kellogg’s stock tumbling from a split-adjusted $50 in 1997 to $20 in 2000. The foundation, as a consequence, shriveled, to $4.85 billion in assets that year from $7.5 billion in 1997. This dismal period is what spurred Lawler to redesign the portfolio.

With two thirds of his holdings in one stock, Lawler must take pains to ensure that the remaining third is noncorrelated. He had already begun hiring what is now a bullpen of more than 50 external managers, 17 of whom run hedge funds, and had increased the allocation to alternatives — hedge funds, venture capital, private equity, natural resources and real estate.

By 2003 he had thrown out the textbook investment models and designed a flexible compilation of assets that allowed his team to easily move the dials on 30 percent of the diversified portfolio. “We’re inherently an absolute-return investor — a hedge fund,” explains investment director Bill Ziomek, who helped design the strategy as a Bank of New York consultant to the foundation before Lawler hired him in February 2008. (Ziomek is part of a four-member management team that includes Lawler.)

Unlike public or corporate pension funds, which can turn to taxpayers or the corporate treasury, and unlike college endowments — which raise money from alumni and other donors — the Kellogg Foundation is self-generating. “The pressure to grow performance is enormous,” says Lawler. But the means to do so are limited because of the heavy tilt toward Kellogg stock, and change is not likely because the foundation’s ties to the company are so strong (the trust that oversees all assets includes Kellogg Co. chairman James Jenness).

“In every meeting of the trustees, there is a resolution and a vote to reaffirm the holding of Kellogg stock,” explains Sterling Speirn, the foundation’s president and CEO. “It’s not a debate; it’s much more a ritual.”

Paul Lawler was the third son in a family of six boys raised in Woodbridge, Connecticut, where his mother managed the household and his father was an executive at tire manufacturer Uniroyal. Lawler attended Yale University, competing on the swim team and graduating with a BA in architecture and political science in 1970. Late in his tenure at Yale, he took a sharp turn when a J.P. Morgan & Co. campus recruiter made him an offer he couldn’t refuse — a job as a junior bank officer in commercial lending and corporate finance.

“I hadn’t taken one course in banking, finance or accounting,” recalls Lawler, but the recruiter called him twice — to wish him good luck before, and congratulations after, an NCAA swim meet. “I said to myself, ‘Any firm that shows this kind of interest in their people is a firm I’m interested in.’”

After seven years at J.P. Morgan, Lawler moved to Columbia University as treasurer and assistant vice president of finance, then to Troy, New York, in 1985 to head up the endowment at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. In 1997, Richardson, former president of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, tapped Lawler to start up a new investment office at the Kellogg Foundation, where Richardson had recently assumed the presidency.

Lawler was still a one-man shop when he crafted his makeover in 2003, though he had support from Ziomek and a team from Boston-based consulting firm Cambridge Associates. They divvied up the diversified assets according to three broad functions: asset preservation (20 percent), stable cash flow (17 percent) and capital appreciation (63 percent). Nearly a third of the diversified assets were set up so that positions could be changed quickly, depending on market conditions. Two recent examples: The allocation to private equity was lowered to 3 percent from 5 percent, and commitments to distressed securities were increased to 10 percent from 5 percent.

Beneath Lawler and his team’s unassuming, Midwestern façades beat the hearts of iconoclasts. “We chose to create our own models of opportunity, risk and function and do that in full recognition of the textbooks and what academics would purport to be concerns of an institutional investor,” explains Ziomek, who questions the views of mainstream economists, including people like Nobel Prize–winner William Sharpe, who invented the Sharpe ratio, the popular formula that calculates how well the returns on an asset compensate an investor for the risks. “His ideas don’t work here,” Ziomek says.

Rather than following the old-school method of doling out allocations by cookie-cutter asset buckets, the foundation’s diversified portfolio allows for rebalancing with functionality in mind. “You fill up buckets whether it’s a good idea or not,” investment director Malcolm Goepfert says of the traditional approach. “It’s kind of perverse because if you’re compensated by the return of your asset class and paid relative to a benchmark, you’re not concerned with absolute returns, but relative returns.”

He explains the Kellogg approach this way: “Here you pay attention to what will make money on an absolute-return basis.”

For example, instead of maintaining a static 10 percent allocation to fixed income, Kellogg might put global bonds in its stable-cash-flow portfolio, where they rub shoulders with a real estate allocation.

So radical was the portfolio redesign in its rearrangement of the taxonomy of investing that Lawler insists he has trouble naming the 17 hedge fund managers the endowment uses because he says he views the portfolio as a single entity — though individuals are assigned to subportfolios that reflect their utility to the overall investment strategy, which, of course, is absolute return.

“I couldn’t tell you how much in alternatives we have,” Lawler says with what is no doubt a measure of disingenuousness. “I would argue respectfully that the question isn’t that relevant any more. It’s all embedded, it’s everywhere. Hedge funds are a fee structure, not an asset class.”

And Lawler’s team says it sees growing pressure on hedge funds to lower those fees. “The business model is broken,” says investment director Goepfert. “It’s not sustainable.”

The hedge fund managers Kellogg hires get a 1 to 2 percent management fee and a 20 percent performance fee, an expense Lawler questions. “Our hedge funds have preserved capital better than long-only managers and broader markets,” he says, “but they’re not all up.”

Goepfert puts it more bluntly: “Why pay one and 20 when most hedge funds are facing redemptions?”

Lawler sometimes considers fees a make-or-break issue. He has rejected managers despite his interest in their strategies after concluding that their fees were too high to allow a reasonable return. But he has a strong kinship, in some respects, with the psychology of hedge funds. Most of the investments under Lawler’s care are less than transparent; he believes, as do most fund managers, that revealing exact investments is giving away the keys to the kingdom. He rarely says which managers he hires, so the description of his holdings tends toward the generic.

Within the foundation’s three primary portfolios — asset preservation, stable cash flow and capital appreciation — are subcategories and sub-subcategories. For example, liquidity, inflation protection and deflation are lumped under asset preservation. Drill into the inflation-protection sub-subcategory to find natural resources —

7 percent of the total diversified portfolio — and there you will also find three hedge funds: one energy fund and two natural-resources funds.

The majority of Kellogg’s hedge fund holdings, however, are in the capital appreciation portfolio, which in mid-January contained almost two thirds of the foundation’s diversified assets. A subcategory there — global marketable equity — has 43 percent of all diversified assets. It includes holdings in five hedge funds: one global core fund and four long-short equity funds, one of which is dedicated to emerging markets. The emerging-markets category is long-short rather than long-only, in hopes of dampening the risks in that arena. (This manager was down 25 percent in 2008, which sounds bad but was better than the 50 percent losses across most of that sector.)

Three New York–based special-situations, distressed-asset hedge funds that invest in marketable assets — which can be traded publicly — are part of the capital appreciation portfolio: Avenue Capital, Davidson Kempner Institutional Partners and Angelo Gordon & Co. The foundation invests too in nonmarketable distressed funds, including six run by Los Angeles–based Oaktree Capital Management, which offers both hedge funds and private equity funds. Kellogg favors the latter, recently investing in three Oaktree offerings: a power infrastructure fund, a mezzanine fund and a fund that invests in European distressed corporate debt.

Lawler doesn’t like paying hedge fund fees but says that some are worth it. “Our goal is not to mimic the market, not to generate market returns, but to produce a stable level of earnings, so we’re willing to sacrifice,” he explains.

He considers it acceptable that hedge funds finished 2008 so far down (the Hedge Fund Research composite index was off by 18.65 percent). “We would expect their return in a down market to be half the decline of the market,” he says. “Nobody’s immune to a market downturn unless you’re an aggressive short-seller.”

Still, losing money in hedge funds may be particularly painful to investors like Lawler, who have always taken a wary view of hedge funds — avoiding leveraged ones, for instance, and their promise of high returns. Kellogg maintains a big cash buffer — 5 percent of the diversified assets — and keeps 70 percent in holdings that can be quickly converted to cash. Lawler is openly critical of the recklessness that has characterized much of institutional investing in recent times. “It hasn’t been popular in the past 15 years to look at the balance sheet,” he says. Lawler cut his teeth at the Columbia University job, developing an in-house investment management style, buying stocks, bonds and real estate rather than farming out the decision making. “I think we’re actually coming back to this — institutions may start investing for themselves again,” he notes, arguing that many external managers have proved too costly and too unproductive.

The key to the in-house approach, he says, is to have an exceptional staff and to persuade trustees that there is a cost advantage.

Lawler says the foundation is especially alert now to opportunities that come out of the credit crisis. Redemption-related asset losses at hedge funds, for instance, have opened the doors to formerly hard-to-access funds. “We’ve talked about the potential opportunity to upgrade the managers we have, but we haven’t pursued that yet,” says Goepfert. “We’ll probably do that over the next year. We want to get into strategies we think long- term are a better fit for the portfolio.”

Lawler and company are looking in particular at long-only fund managers that may be able to take advantage of a stock market that by mid-February had fallen some 40 percent in a few months’ time. His team is on it already, spending 30 to 40 percent of its time visiting managers who rarely come to Battle Creek. Lawler prefers it that way — he says managers need to keep their noses to the grindstone and let his people come to them.